Transatlantic Conversations: Black Renaissance Pianism across the Pond

The Black Renaissances of Harlem, Chicago, Philadelphia, Detroit and all of the urban centers where Black creatives and intellectuals thrived, not only ushered in an era of rebirth, but also one of reconnection. If rebirth was about people of African descent establishing a new and empowered sense of how to move forward against the tyranny of Jim Crow, then reconnection was about drawing strength from the past and harnessing the beauty and power of ancestral traditions. Transatlantic Conversations: Black Renaissance Pianism across the Pond explores these themes of rebirth and reconnection, journeying through the ancient world of the Moors to plantation dances of the enslaved, and through the classical music cultures of Europe to Afrocentric reshapings of North America.

Read more

Although the Black Renaissance reflects a unique period in U.S. history, it also encompasses the foundational work of the British Samuel Coleridge-Taylor and Canadian Robert Nathaniel Dett, both of whom developed a musical style that would inspire new generations of African American composers. Coleridge-Taylor was a mixed-race composer, violinist and conductor of both English and Sierra Leonean descent, on his mother’s and father’s side, respectively. Many of his works drew influence from Black folk songs, which proved empowering for Black composers in the States. Coleridge-Taylor used the word “Negro” with pride when he wrote his 24 Negro Melodies in 1905.

The piece that opens Transatlantic Conversations is Coleridge-Taylor’s Moorish Dance, which was published the year before 24 Negro Melodies. Again, the term Moor took on derogatory connotations in relation to people of African descent. However, Coleridge-Taylor restored pride and power with a work that is both regal and grand. When you hear Coleridge-Taylor’s Moorish Dance, you will see why the revival of ancient Black histories and traditional folk heritages resonated so deeply in an era that epitomized rebirth and reconnection.

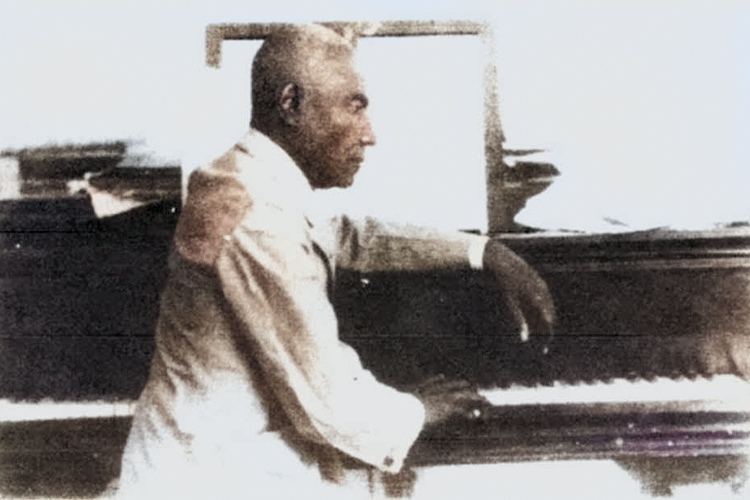

Coleridge-Taylor’s treatment of Black folk songs revealed greater possibilities for Robert Nathaniel Dett. Like Coleridge-Taylor, Dett was a product of the Romantic tradition—a tradition characterized by lyrical melodies, impassioned harmonies and dramatic flair. But, also like his British predecessor, Dett was inspired by the narratives of 19th-century Black life, as celebrated in his piano suite In the Bottoms.

Similar to Dett’s piano suite, Harry T. Burleigh’s From the Southland is another evocative portrait of Black Antebellum life. Burleigh was predominantly known for his art song compositions and international performance career. His piano suite is a rare work that showcases his brilliance as a composer of piano music. However, the vocal element is still there as each movement of the suite is prefaced by a spoken passage in African American vernacular dialect. Additionally, Burleigh dedicates this work “To my friend S. Coleridge Taylor Esq.”

Nora Holt’s Negro Dance builds on the creative legacies of those who came before her. It draws inspiration from 19th-century plantation dances, most notably the Pattin’ Juba (which we also hear in Dett’s In the Bottoms). Negro Dance is Holt’s only surviving work for solo piano. At some point during the 1920s, she kept her music in storage while she studied in Paris with Nadia Boulanger. Holt returned home to find her belongings had been ransacked, but Negro Dance survived as it was one of the few pieces she published elsewhere.

Transatlantic Conversations comes full circle with the music of Amanda Aldridge, a mixed-race British composer—daughter of the famed African American Shakespearean actor Ira Aldridge (whose portrait hangs in London’s National Portrait Gallery) and the Swedish Amanda Brandt. Like Coleridge-Taylor, Aldridge studied at the Royal College of Music and immersed herself in the country’s flourishing classical scene. Aldridge brings us to the Africa of her imagination with her Three African Dances. Put together, each piece illuminates the rich tapestry that emerges from these transatlantic threads.

Dr. Samantha Ege is an award-winning musicologist, internationally recognized concert pianist and Anniversary Research Fellow at the University of Southampton. Her forthcoming book is called South Side Impresarios: Race Women in the Realm of Music (University of Illinois Press) and her latest album is available now and called Homage: Chamber Music from the African Continent and Diaspora, featuring the music of Bongani Ndodana-Breen, Undine Smith Moore, Samuel Coleridge-Taylor, Zenobia Powell Perry and Frederick C. Tillis.

Introducing 36 Keys

by Samantha Ege

36 Keys: A Collection of Piano Works by Black Composers launches by illuminating the kaleidoscopic output of African-descended composer-pianists who inspired and galvanized the Black Renaissance era. With an initial offering comprising works by Florence Price, Louis Moreau Gottschalk, Irene Britton Smith, Hazel Scott, Ludovic Lamothe, Mary Lou Williams, Jelly Roll Morton and Fats Waller, this dynamic musical era in American history is wondrously brought to life. From rhapsodic classical movements to rollicking jazz, 36 Keys captures the vibrancy of the Harlem Renaissance and beyond.

Read more

The Black Renaissance at large unfolded through the first half of the twentieth century. Growing out of urban centers such as New York’s Harlem and Chicago’s South Side and reverberating across the African diaspora, the Black Renaissance saw thinkers and visionaries of African descent bring about a rebirth in all aspects of life and identity. Whether it was through music, art, dance, literature, or theatre, the expressive arts were important vehicles for cultural reinvigoration and social transformation.

Composers used their craft to articulate their power as creative intellectuals. From “Spirituals to Symphonies” (to quote the composer, activist, and Black Renaissance woman Shirley Graham DuBois), Black musicians demonstrated their talent and authority in a wide range of genres. There were many composer-pianists during this time who were classically trained, either through the musical networks in their communities or at prominent conservatories in the United States and abroad. Their musical foundations were often a mix of European techniques and African American folk and popular music influences. With Black vernacular styles and the multiple genres they birthed being so heavily disparaged in mainstream American culture, a number of composers operating during this time sought to affirm that the Black American folk tradition was a vital history that still spoke to the hopes and dreams of every generation that followed.

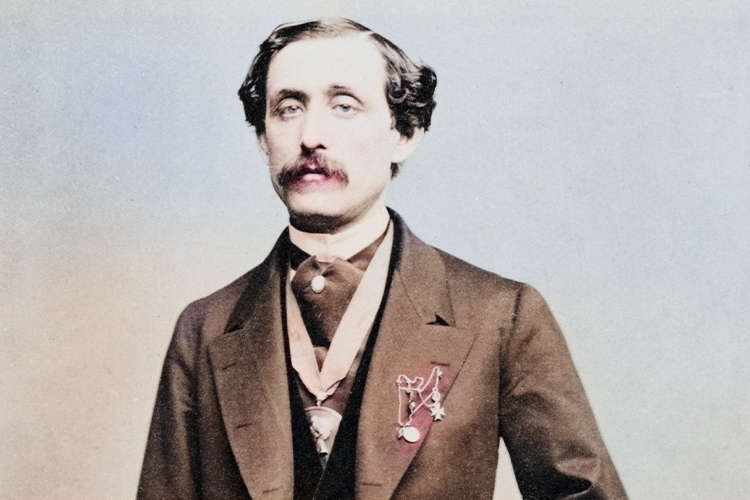

The presence of Haitian composer Ludovic Lamothe connects the Black Renaissance to broader cultural movements across the African diaspora. Lamothe, like his counterparts in the United States, found rich inspiration in the folkloric cultures of his home country and in the nineteenth-century piano tradition. Parallels can further be drawn between him and the nineteenth-century Romanticist Louis Moreau Gottschalk, who wowed audiences with his virtuosic renditions. While Gottschalk, by virtue of his much earlier birth date, is an outlier with regard to the Black Renaissance era, his influence was felt throughout.

Gottschalk took Creole themes and other folk influences as inspiration for his craft. Many Black Renaissance composers later did the same, drawing upon the melodic contours of the Negro Spirituals and the rhythmic patterns of plantation dances for inspiration, or innovating new popular music genres based on earlier African American folk styles. No more is this blend of the virtuosic and vernacular more evident than in the featured piano music on this program. Gottschalk is therefore a necessary reminder of how long the history and legacy of African-descended composers run.

A program capturing the expansiveness of the Black Renaissance would be incomplete without the voices of jazz pioneers Jelly Roll Morton, Mary Lou Williams, Fats Waller and Hazel Scott. They blurred musical boundaries with their boldly chromatic and strikingly syncopated soundscapes. They broke racial barriers and, in the case of Williams and Scott, empowered female voices. With each improvisation, they pushed jazz into new realms of sonic creativity and political expression. The transcriptions of their much-loved compositions featured in this program allow today’s audiences to experience the excitement of their live performances.

Florence Price, Jelly Roll Morton and Ludovic Lamothe—all born toward the end of the nineteenth century—represent a distinct generation of composer-pianists whose artistry flourished during the Black Renaissance era. The next generation of composer-pianists (born in the first few decades of the twentieth century)—Fats Waller, Irene Britton Smith, Mary Lou Williams and Hazel Scott—were sons and daughters of the Black Renaissance. They expanded the sound worlds of their predecessors as they ventured toward new, expressive heights. 36 Keys thus proudly celebrates more than a century of Black pianistic voices.